Chapter 2

CHAPTER 2

THROUGH THE MIDDLE AGES

“…such beautiful minds…”

Let us leave behind the early scientists like the honored Hypatia and En’Hedu’anna and travel forward in time through the Dark Ages and Middle Ages. I want to share some stories of the women who persisted and succeeded by following her shining example.

In imperial Rome women could be seen carrying copies of Plato’s Republic because it touted education for women. In general the status of women in ancient Rome was a bit better than their sisters’ status in ancient Greece. It was not unusual for a young girl of plebian parentage to attend elementary school. Upper class men and women had private tutors. Among the attributes of a good wife was her ability to converse intelligently on philosophy and geometry although the true bluestocking (scholar) was probably rare. And, as happened in Greece, many women were known as worthy poets and orators. All over the empire of Rome women of wealth and influence functioned as benefactors and participants in the public world. For example, in the 4th century the young woman Eustochium edited Jerome’s translation of the Bible, the future Latin Vulgate .

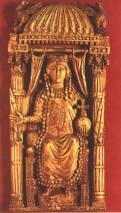

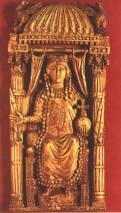

In 337 CE the Roman Empire was split among the three sons of Constantine into eastern, western, and central. In 475 CE Romulus Augustus became the last of the western Roman emperors. He abdicated a year later, and the western Roman empire came to an end. Yet the barbarians who conquered Rome were not slothful scholars. The daughter of the first Ostrogothic king of Rome (Theordoric the Great), Amalsuntha (498 – 535 CE), could converse in Latin, Greek and Gothic. She ruled the Ostrogothic (Roman) empire when her father suddenly died. An ivory representation of Amalsuntha is shown on the left. In 535 CE her cousin usurped the throne and had her killed. Less than two years later the Byzantine emperor Justinian invaded Italy to avenge her death, ending the Ostrogothic rule in Italy. He also closed the hundreds of years old school of philosophy in Athens – the wonderful Academy of Plato founded in 387 BCE. Many of the professors went to Persia and Syria. But it was a loss to scholarship.

Despite the loss of the Academy of Plato and despite the destruction of the Great Library of Alexandria, the wisdom of women and men lit with rare, flickering candles of scholarship the Dark Ages that followed the fall of the Roman Empire.

As always, women kept their medical tradition alive even in those Dark Ages. For example, in Constantinople medicine (and philosophy) gave us the physician Nicerata. Jumping ahead a bit – seven hundred years later, interestingly, one of the best equipped hospitals of the time was built in Constantinople by Emperor John II (1118 – 1143 CE). Men and women were housed in separate buildings, each containing ten wards of fifty beds, with one ward reserved for surgical cases and another for long-term patients. The staff was a team of twelve male doctors and one fully qualified female doctor as well as a female surgeon. I don’t know their names but they existed. It was not the first large hospital in the area though. In 1096, the first Crusade bought a need for expanded medical facilities in Constantinople. The emperor Alexius built a 10,000 bed hospital/orphanage managed by his daughter Anna Comena. She had been well trained by tutors in astronomy, medicine, history, military affairs, history, geography, and math. Running a hospital must have been easy for her. She also wrote a history of her father’s life. Called the Alexiad this document forms a primary resource for the first Crusade.

Italian women continued to contribute to medicine. The first Western type university was founded in Salerno, Italy in 875 CE as a medical school. And from that time to this, for over a thousand years, women equally with men have been welcome at the doors of Italian universities. So it is not remarkable that there were so many talented Italian women. As early as 1292 there were in Paris no less than eight physicians who were women although they were not quite the scholars their Italian sisters were. Jacobina Félicie (c. 1322 CE) was born in Florence and worked in Paris as a physician. She ultimately lost her battle to practice medicine thus setting a precedent against women attending medical school in France unbroken until the 1800’s. A number of the Italians are listed in this paragraph. Trotula lived in the 11th century and held a chair in the school of medicine at the University of Salerno. The Regimen sanitatis salernitatum contained many contributions from her work and was widely used well into the 16th century. She promoted cleanliness, a balanced diet, exercise, and avoidance of stress – a very modern combination. Salerno was home to other women of medicine including Abella, Rebecca de Guarna, Margaritan, and Mercuriade (all 14th century CE). Among those who held diplomas for surgery were Maria Incarnata of Naples and Thomasia de Mattio of Castro Isiae. Alessandra Giliana (c. 1318 CE) was an anatomist at the University of Bologna. Dorotea Bucca (1360 – 1436 CE) held a chair of medicine at the University of Bologna. Laura Ceretta (1469 – 1488 CE) gave public lectures on philosophy. Battista Malatesta (1383 – 1450 CE) of Urbino taught philosophy as well. Calrice di Durisio (15th century CE) was a surgeon who specialized in diseases of the eye.

That is one thousand years at a gulp. Let me back up and travel a bit more slowly.

The major religions tended to claim separate parts of the known world. Christianity spread throughout western Europe after 313 CE when Constantine’s Edit of Milan proclaimed it tolerated throughout the Roman Empire. Islam became strong in Western Asia after 622 CE (the Hegira of Mohammed). In 732 CE at Tours, France, Charles Martel stopped the expansion of Islam into western Europe. The works of Confucius dominated in China. The Buddhists grew more numerous and spread out from India to China and beyond.

Looking at the Far East, a queen of Korea, Sonduk (c. 630 CE), built astronomical observatories. One of her observatories called the Tower of the Sun and Moon stood until the 20th century. Chinese women were inventive. Around 577 CE the first version of matches were invented by the women of the northern Ch’i province in China. They were under siege and needed to start fires for cooking. Moving to the Middle East, during the 13th century over 100 women taught at levels equivalent to a professorship at Dervis monasteries (Turkey) in the Islamic world. Names of two such teachers are Fatima-bint’Abbas and Zeynep. But other than those small bits of information I know very little about the Middle and Far East and Africa.

So this is a limited story, limited by my ignorance. I believe there are wonderful women to find in those other cultures.

Coming back to the decline of Rome, as the Dark Ages drew across Europe centers of learning, abbeys and convents usually associated with the expanding Christian church were built. For example, in France, Queen Radegund (518 – 587 CE) forsook her royal state and founded an abbey for women at Poitiers, France. She was quite interested in medicine and had the quite radical notion of washing the patient clean! For the following several hundred years such abbeys were the refuge of women who wished to follow a separate way filled often with scholarship as well as prayer.

By 800 CE many Christian monasteries, abbeys, and convents existed for the devout woman of the Western world. These places became great settlements that encouraged scholarship as well as piety. The abbey women, along with their male counterparts, copied and recopied the studious works of the day as well as the rare literature of the past, maintaining them for Western posterity. Many of the women were illustrators as well as copiers of manuscripts. These illuminations on the manuscripts were things of outstanding beauty.

By joining one of these great settlements women could be free of the intellectual restrictions put on their sex by the secular world. From the 7th to the 11th centuries abbesses held the same power as their male counterparts, in both the secular as well as the religious realm. The larger religious settlements usually owned the surrounding lands as well as actual convent buildings. The abbesses had the right to attend ecclesiastical synods and assist in the deliberations of national assemblies. Some even had the right to coin money and raise armies. To put this into 21st century terms, the career opportunities for some women during this time were perhaps greater than they are today. A bold statement, but worth considering.

This illumination is adapted from Hildegardis Bingensis. Liber Divinorvm Opervm. Ed. A. Derolez and Peter Dronke. Turnout: Brepols, 1996.

Often the convents and abbeys would conduct schools to which privileged children, both female and male, came. Literacy in these days meant reading and writing in Latin and sometimes Greek and Hebrew. Ida (c. 570 CE) of Ireland founded a community of nuns who taught a school for small boys including the future missionary, St. Brendan, also known as Brendan the Voyager. Abbess Aelfthrith (c. 694 CE) built Repton in Derbyshire, England into a center for education. Abbess Hilda (616 – 680 CE) made Whitby, England, a settlement of men and women, into a center of learning. As chief educator she taught theology, grammar, music, the arts, and medicine. During the 7th and 8th centuries there were over thirty English abbesses who ran monasteries. An English nun, Leoba (died 779 CE), because of her learned reputation, was sought out by other church leaders for advice. Around 733 CE, her cousin Boniface asked her to help him in his church building efforts in Germany. She agreed and was appointed abbess at Bishofscheim in Germany. For forty years she taught the young nuns there and was sought by many for her wisdom and knowledge. She was friend and counselor to Hildegard, the wife of Charlemagne. Women’s contributions lasted for over eight hundred years. Around 1290 CE Claranna von Hohenburg, a Swiss nun, was said to be advanced in scientific knowledge.

One woman, Hrotsvit of Gandersheim (c. 930 – c. 990 CE) in Saxony wrote verse, history, and the only dramas composed in Europe from the 4th to the 11th centuries. She was allowed her own court, the right to coin money, and to sit at meetings of the Diet – the ruling body. She is usually known by the Saxon equivalent of her self-styled pen name, Hroswitha: hroth meaning ‘sound’ and swith meaning ‘loud’ or ‘strong’ – she who makes a strong sound.

Towards the end of the Dark Ages the Islamic world surpassed the Western world in its access to technical literature. One can easily find information about male Islamic mathematicians and scholars. I know of no technical Islamic women from those times. There may be, indeed, many women to include, but I have no information on them.

The Dark Ages gave way to the Middle Ages as social structures swirled about, settling into new patterns. Feudal Europe became a centuries old war-torn land as rulers continued to fight over boundaries and land rights. At the same time, Europeans attempted to retake control of Jerusalem. The crusades to Palestine forced open cultural doors long closed. Genghis Khan (1155 – 1227 CE) united the Mongols and swept across the steppes and destroyed ancient centers of civilization in eastern Europe. Less than a century later, Marco Polo (1254 – 1354 CE) reached China continuing to open cultural doors.

Women continued to contribute their scholarship despite the shifting sands beneath their feet. Herrad of Landsberg (1125 – 1195 CE) was abbess of the convent of Ste Odile in Hohenbourg and compiler-illuminator of the Hortus Deliciarum (The Garden of Delights). This large folio consisted of 324 pages and 636 miniature illustrations that depicted biblical scenes and allegorical figures. In it there are over a thousand texts by different authors on different subjects including poems by Herrad herself – a compendium of medieval learning of the knowledge and history of the world intended for the women in her convent. This encyclopedic work covered biblical, moral and theological material.

The seven liberal arts adapted from the Hortus Deliciarum.

http://www.kefk.net/Wissen/Werke/H/Hortus.deliciarum/index.asp

One truly shining light stands out from the rest – that of Hildegard of Bingen-am-Rhein (1098 – 1179 CE). One of our rare true geniuses, she was a mystic who wrote volumes of text, composed music, painted, and ran her convent. A web search on her name will turn up over a million hits.

She was sent to the convent as a young child. While there she wrote in her journal speaking of her nurse

“This wonderful woman who had guided me in observing the range of positions of the rising and setting Sun, who had had me mark with a crayon on a wall the time and place where the warming sunlight first appeared in the morning and finally disappeared each and every day of my eleventh year.”

This is the mark of the true scientist.

Her first visionary work was Scivias ("Know the Ways of the Lord"). She wrote the music and play Ordo Virtutum (Play of Virtues). She also wrote Liber vitae meritorum (1150 – 63 CE) (Book of Life's Merits) and Liber divinorum operum (1163 CE) (Book of Divine Works).. She also authored Physica and Causae et Curae (1150 CE), both works on natural history and curative powers of various natural objects, which are together known as Liber subtilatum (The book of subtleties of the Diverse Nature of Things). Physica was actually nine books treating minerals, plants, fishes, birds, insects, and quadrupeds. The book on plants has no fewer than two hundred and thirty chapters. Kass-Simon and Farnes have an excellent description of her natural history work in their book Women of Science Righting the Record .

Her music has been recorded on several CDs. She wrote eerily beautiful Gregorian chants, some so enthralling that it is said that people would faint upon hearing her music. She expanded plainchant (a unison chant, originally unaccompanied) a bit beyond the basic intricacies of Gregorian Chant even though she had no formal music training.

She is honored by nurses as the founder of holistic medicine, and delightfully mixed a wonderful common sense with her healing. Here is her recipe for spice cookies (modernized).

“Eat them often,” she says, “and they will calm every bitterness of heart and mind - and your hearing and senses will open. Your mind will be joyous, and your senses purified, and harmful humours will diminish.”

3/4 cup butter or margarine (1 1/2 sticks), 1 cup brown sugar, 1 egg, 1 tsp baking powder, 1/4 tsp salt, 1 1/2 cups flour, 1 tsp ground cinnamon, 1 tsp ground nutmeg, 1/2 tsp ground cloves. Mix, form walnut sized balls, and bake for 10-15 minutes.

She wrote that

“The stars gravitate around the Sun just as the Earth attracts the creatures which inhabit it”

This is the concept of universal gravitation as we know it now, long before it became a standard part of mathematics (five hundred years later by Sir Isaac Newton). She also wrote

“If it is cold in winter time on the part of the Earth which we inhabit, then the other part must be warm, in order that the temperature of the Earth may always be in equilibrium”

adapted from Hildegard of Bingen, Symphonia Harmonie Celestium Revelationum, published in modern facsimile by Alamire, POB 45, 3990 Peer, Belgium

This shows a remarkable sense of the synergy of the Earth. Today we call this point of view thermodynamics. And forecasting Harvey’s theory of blood movement through the body as well as the concept of universal gravitation she wrote:

“Stars are not immovable but transverse the universe in a manner similar to blood moving through the body.”

My favorite quote is about her belief in the healing power of gems.

“A precious gem will heal the body if taken to bed. And a diamond held in the mouth of a liar or scold would cure any spiritual defects.”

Definitely something worth following up.

Hildegard was a special woman, talented in many, many fields. She corresponded widely with the learned men and women of the day and was highly sought after for advice. She was brave in her writings. There is a letter from her to Pope Anastasius IV that begins

“So it is, O man, that you who sit in the chief seat of the Lord, hold him in contempt when you embrace evil …”

She was one of the shining lights of the early Middle Ages. Her books were instant “bestsellers”.

Another of her beautiful illuminations is shown above.

During this time Italy continued its unique tradition of allowing women in the university. In 1236 CE Bettina Gozzadini was appointed to the Chair of Law at the University of Bologna. A century later Novella d’Andrea frequently substituted for her father, a professor of law at the same university. But more about Italy later.

As we move forward in time we find a few women who worked in traditional male occupations. Fya upper Bach was a 14th century blacksmith in Siberg, Germany. Twice in her career she held office in the local blacksmiths’ guild. Mary Sidney Herbert (1561 – 1621 CE), Countess of Pembroke, was quite a learned lady. She was known for her chemistry as well as her poems. One of the leading male chemists of the day – Adrian Gilbert – called her a chemist of note. Women were inventors too. Isabella Cunio (13th century CE) may have been the co-inventor with her brother of woodblock engraving.

It is extremely difficult to find names from the far East and India during this time. Did women of scholarship exist? I think so, but their names are deep in untranslated documents. Two names only have I found. One is the daughter of the Indian mathematician Bhasharacharya (1114 – 1185 CE). He did many important things in astronomy and mathematics including resolving a problem with the number zero. He was the first to note that division by zero did not give zero; it resulted in infinity. He wrote several texts on math, one of which he named after his daughter Leelavati (“Beautiful”). The book was used to teach her algebra. She was also an excellent mathematician. In 1816 this book was translated into English. The other is Raziya. Shortly after Leelavati lived, Raziya became the first Muslim lady to rule a Moslem state – she was Sultana of Delhi in 1236 CE and very well educated.

I shall end this chapter with a note about a woman who was not a scientist but was perhaps the first woman in Europe to earn her living through her writing – Christian de Pisan (1363 – 1429 CE) . Widowed at twenty-five with a large family to support she took the bold step of going her own way. She wrote at least twelve books and ten works in verse, including what is perhaps the first history of women in the European world – The Book of the City of Ladies. This is a fascinating book that combines legend with reality in a sweeping allegory of a city of ladies. Her works are still studied today. I found a tidbit in this book that continues to enchant me. It is a puzzling statement about the education of women.

“God has given them such beautiful minds to apply themselves, if they want to, in any of the fields where glorious and excellent men are active, which are neither more nor less accessible to them as compared to men if they wished to study them, and they can thereby acquire a lasting name…”

Did she mean that women had the same opportunities as men in the 14th century? I don’t know. It is fascinating to speculate. Nonetheless it is always true that most women and men were scrabbling for mere existence in these centuries.

The times leading to the Renaissance were times of extreme change in social customs. The black death decimated whole towns bringing cultural change with it because the plague upset the social order (especially in the 14th century, see next chapter). It was a struggle just to survive for the vast majority of people. Slowly, the Roman Catholic Church solidified its beliefs, and over time the stultifying religious view of women’s inferiority overcame the freeing winds of the convent. The Christian church consolidated its power becoming the major claimant in most peoples’ lives. Church fathers wrote polemics against women, especially women scholars. The great convents were destroyed or shut down. The profits of centuries of learning and effort were snatched away. Men shut down the convents, destroyed the manuscripts, took the money and lands and created new universities on the ashes. The great witchcraft mania began, not to end until the 18th century. Until the 14th century men and women of the feudal nobility received approximately the same elementary education. With the rise of the university system in Europe that custom declined. Where religion once supported women in scholarship, it now denied them access. One had to be a member of the clergy to attend the university, and women were denied that right.

Despite Christian de Pisan’s statement that women have such beautiful minds, rights for women declined with one large exception. Let us travel a bit further along in time.

THROUGH THE MIDDLE AGES

“…such beautiful minds…”

Let us leave behind the early scientists like the honored Hypatia and En’Hedu’anna and travel forward in time through the Dark Ages and Middle Ages. I want to share some stories of the women who persisted and succeeded by following her shining example.

In imperial Rome women could be seen carrying copies of Plato’s Republic because it touted education for women. In general the status of women in ancient Rome was a bit better than their sisters’ status in ancient Greece. It was not unusual for a young girl of plebian parentage to attend elementary school. Upper class men and women had private tutors. Among the attributes of a good wife was her ability to converse intelligently on philosophy and geometry although the true bluestocking (scholar) was probably rare. And, as happened in Greece, many women were known as worthy poets and orators. All over the empire of Rome women of wealth and influence functioned as benefactors and participants in the public world. For example, in the 4th century the young woman Eustochium edited Jerome’s translation of the Bible, the future Latin Vulgate .

In 337 CE the Roman Empire was split among the three sons of Constantine into eastern, western, and central. In 475 CE Romulus Augustus became the last of the western Roman emperors. He abdicated a year later, and the western Roman empire came to an end. Yet the barbarians who conquered Rome were not slothful scholars. The daughter of the first Ostrogothic king of Rome (Theordoric the Great), Amalsuntha (498 – 535 CE), could converse in Latin, Greek and Gothic. She ruled the Ostrogothic (Roman) empire when her father suddenly died. An ivory representation of Amalsuntha is shown on the left. In 535 CE her cousin usurped the throne and had her killed. Less than two years later the Byzantine emperor Justinian invaded Italy to avenge her death, ending the Ostrogothic rule in Italy. He also closed the hundreds of years old school of philosophy in Athens – the wonderful Academy of Plato founded in 387 BCE. Many of the professors went to Persia and Syria. But it was a loss to scholarship.

Despite the loss of the Academy of Plato and despite the destruction of the Great Library of Alexandria, the wisdom of women and men lit with rare, flickering candles of scholarship the Dark Ages that followed the fall of the Roman Empire.

As always, women kept their medical tradition alive even in those Dark Ages. For example, in Constantinople medicine (and philosophy) gave us the physician Nicerata. Jumping ahead a bit – seven hundred years later, interestingly, one of the best equipped hospitals of the time was built in Constantinople by Emperor John II (1118 – 1143 CE). Men and women were housed in separate buildings, each containing ten wards of fifty beds, with one ward reserved for surgical cases and another for long-term patients. The staff was a team of twelve male doctors and one fully qualified female doctor as well as a female surgeon. I don’t know their names but they existed. It was not the first large hospital in the area though. In 1096, the first Crusade bought a need for expanded medical facilities in Constantinople. The emperor Alexius built a 10,000 bed hospital/orphanage managed by his daughter Anna Comena. She had been well trained by tutors in astronomy, medicine, history, military affairs, history, geography, and math. Running a hospital must have been easy for her. She also wrote a history of her father’s life. Called the Alexiad this document forms a primary resource for the first Crusade.

Italian women continued to contribute to medicine. The first Western type university was founded in Salerno, Italy in 875 CE as a medical school. And from that time to this, for over a thousand years, women equally with men have been welcome at the doors of Italian universities. So it is not remarkable that there were so many talented Italian women. As early as 1292 there were in Paris no less than eight physicians who were women although they were not quite the scholars their Italian sisters were. Jacobina Félicie (c. 1322 CE) was born in Florence and worked in Paris as a physician. She ultimately lost her battle to practice medicine thus setting a precedent against women attending medical school in France unbroken until the 1800’s. A number of the Italians are listed in this paragraph. Trotula lived in the 11th century and held a chair in the school of medicine at the University of Salerno. The Regimen sanitatis salernitatum contained many contributions from her work and was widely used well into the 16th century. She promoted cleanliness, a balanced diet, exercise, and avoidance of stress – a very modern combination. Salerno was home to other women of medicine including Abella, Rebecca de Guarna, Margaritan, and Mercuriade (all 14th century CE). Among those who held diplomas for surgery were Maria Incarnata of Naples and Thomasia de Mattio of Castro Isiae. Alessandra Giliana (c. 1318 CE) was an anatomist at the University of Bologna. Dorotea Bucca (1360 – 1436 CE) held a chair of medicine at the University of Bologna. Laura Ceretta (1469 – 1488 CE) gave public lectures on philosophy. Battista Malatesta (1383 – 1450 CE) of Urbino taught philosophy as well. Calrice di Durisio (15th century CE) was a surgeon who specialized in diseases of the eye.

That is one thousand years at a gulp. Let me back up and travel a bit more slowly.

The major religions tended to claim separate parts of the known world. Christianity spread throughout western Europe after 313 CE when Constantine’s Edit of Milan proclaimed it tolerated throughout the Roman Empire. Islam became strong in Western Asia after 622 CE (the Hegira of Mohammed). In 732 CE at Tours, France, Charles Martel stopped the expansion of Islam into western Europe. The works of Confucius dominated in China. The Buddhists grew more numerous and spread out from India to China and beyond.

Looking at the Far East, a queen of Korea, Sonduk (c. 630 CE), built astronomical observatories. One of her observatories called the Tower of the Sun and Moon stood until the 20th century. Chinese women were inventive. Around 577 CE the first version of matches were invented by the women of the northern Ch’i province in China. They were under siege and needed to start fires for cooking. Moving to the Middle East, during the 13th century over 100 women taught at levels equivalent to a professorship at Dervis monasteries (Turkey) in the Islamic world. Names of two such teachers are Fatima-bint’Abbas and Zeynep. But other than those small bits of information I know very little about the Middle and Far East and Africa.

So this is a limited story, limited by my ignorance. I believe there are wonderful women to find in those other cultures.

Coming back to the decline of Rome, as the Dark Ages drew across Europe centers of learning, abbeys and convents usually associated with the expanding Christian church were built. For example, in France, Queen Radegund (518 – 587 CE) forsook her royal state and founded an abbey for women at Poitiers, France. She was quite interested in medicine and had the quite radical notion of washing the patient clean! For the following several hundred years such abbeys were the refuge of women who wished to follow a separate way filled often with scholarship as well as prayer.

By 800 CE many Christian monasteries, abbeys, and convents existed for the devout woman of the Western world. These places became great settlements that encouraged scholarship as well as piety. The abbey women, along with their male counterparts, copied and recopied the studious works of the day as well as the rare literature of the past, maintaining them for Western posterity. Many of the women were illustrators as well as copiers of manuscripts. These illuminations on the manuscripts were things of outstanding beauty.

By joining one of these great settlements women could be free of the intellectual restrictions put on their sex by the secular world. From the 7th to the 11th centuries abbesses held the same power as their male counterparts, in both the secular as well as the religious realm. The larger religious settlements usually owned the surrounding lands as well as actual convent buildings. The abbesses had the right to attend ecclesiastical synods and assist in the deliberations of national assemblies. Some even had the right to coin money and raise armies. To put this into 21st century terms, the career opportunities for some women during this time were perhaps greater than they are today. A bold statement, but worth considering.

This illumination is adapted from Hildegardis Bingensis. Liber Divinorvm Opervm. Ed. A. Derolez and Peter Dronke. Turnout: Brepols, 1996.

Often the convents and abbeys would conduct schools to which privileged children, both female and male, came. Literacy in these days meant reading and writing in Latin and sometimes Greek and Hebrew. Ida (c. 570 CE) of Ireland founded a community of nuns who taught a school for small boys including the future missionary, St. Brendan, also known as Brendan the Voyager. Abbess Aelfthrith (c. 694 CE) built Repton in Derbyshire, England into a center for education. Abbess Hilda (616 – 680 CE) made Whitby, England, a settlement of men and women, into a center of learning. As chief educator she taught theology, grammar, music, the arts, and medicine. During the 7th and 8th centuries there were over thirty English abbesses who ran monasteries. An English nun, Leoba (died 779 CE), because of her learned reputation, was sought out by other church leaders for advice. Around 733 CE, her cousin Boniface asked her to help him in his church building efforts in Germany. She agreed and was appointed abbess at Bishofscheim in Germany. For forty years she taught the young nuns there and was sought by many for her wisdom and knowledge. She was friend and counselor to Hildegard, the wife of Charlemagne. Women’s contributions lasted for over eight hundred years. Around 1290 CE Claranna von Hohenburg, a Swiss nun, was said to be advanced in scientific knowledge.

One woman, Hrotsvit of Gandersheim (c. 930 – c. 990 CE) in Saxony wrote verse, history, and the only dramas composed in Europe from the 4th to the 11th centuries. She was allowed her own court, the right to coin money, and to sit at meetings of the Diet – the ruling body. She is usually known by the Saxon equivalent of her self-styled pen name, Hroswitha: hroth meaning ‘sound’ and swith meaning ‘loud’ or ‘strong’ – she who makes a strong sound.

Towards the end of the Dark Ages the Islamic world surpassed the Western world in its access to technical literature. One can easily find information about male Islamic mathematicians and scholars. I know of no technical Islamic women from those times. There may be, indeed, many women to include, but I have no information on them.

The Dark Ages gave way to the Middle Ages as social structures swirled about, settling into new patterns. Feudal Europe became a centuries old war-torn land as rulers continued to fight over boundaries and land rights. At the same time, Europeans attempted to retake control of Jerusalem. The crusades to Palestine forced open cultural doors long closed. Genghis Khan (1155 – 1227 CE) united the Mongols and swept across the steppes and destroyed ancient centers of civilization in eastern Europe. Less than a century later, Marco Polo (1254 – 1354 CE) reached China continuing to open cultural doors.

Women continued to contribute their scholarship despite the shifting sands beneath their feet. Herrad of Landsberg (1125 – 1195 CE) was abbess of the convent of Ste Odile in Hohenbourg and compiler-illuminator of the Hortus Deliciarum (The Garden of Delights). This large folio consisted of 324 pages and 636 miniature illustrations that depicted biblical scenes and allegorical figures. In it there are over a thousand texts by different authors on different subjects including poems by Herrad herself – a compendium of medieval learning of the knowledge and history of the world intended for the women in her convent. This encyclopedic work covered biblical, moral and theological material.

The seven liberal arts adapted from the Hortus Deliciarum.

http://www.kefk.net/Wissen/Werke/H/Hortus.deliciarum/index.asp

One truly shining light stands out from the rest – that of Hildegard of Bingen-am-Rhein (1098 – 1179 CE). One of our rare true geniuses, she was a mystic who wrote volumes of text, composed music, painted, and ran her convent. A web search on her name will turn up over a million hits.

She was sent to the convent as a young child. While there she wrote in her journal speaking of her nurse

“This wonderful woman who had guided me in observing the range of positions of the rising and setting Sun, who had had me mark with a crayon on a wall the time and place where the warming sunlight first appeared in the morning and finally disappeared each and every day of my eleventh year.”

This is the mark of the true scientist.

Her first visionary work was Scivias ("Know the Ways of the Lord"). She wrote the music and play Ordo Virtutum (Play of Virtues). She also wrote Liber vitae meritorum (1150 – 63 CE) (Book of Life's Merits) and Liber divinorum operum (1163 CE) (Book of Divine Works).. She also authored Physica and Causae et Curae (1150 CE), both works on natural history and curative powers of various natural objects, which are together known as Liber subtilatum (The book of subtleties of the Diverse Nature of Things). Physica was actually nine books treating minerals, plants, fishes, birds, insects, and quadrupeds. The book on plants has no fewer than two hundred and thirty chapters. Kass-Simon and Farnes have an excellent description of her natural history work in their book Women of Science Righting the Record .

Her music has been recorded on several CDs. She wrote eerily beautiful Gregorian chants, some so enthralling that it is said that people would faint upon hearing her music. She expanded plainchant (a unison chant, originally unaccompanied) a bit beyond the basic intricacies of Gregorian Chant even though she had no formal music training.

She is honored by nurses as the founder of holistic medicine, and delightfully mixed a wonderful common sense with her healing. Here is her recipe for spice cookies (modernized).

“Eat them often,” she says, “and they will calm every bitterness of heart and mind - and your hearing and senses will open. Your mind will be joyous, and your senses purified, and harmful humours will diminish.”

3/4 cup butter or margarine (1 1/2 sticks), 1 cup brown sugar, 1 egg, 1 tsp baking powder, 1/4 tsp salt, 1 1/2 cups flour, 1 tsp ground cinnamon, 1 tsp ground nutmeg, 1/2 tsp ground cloves. Mix, form walnut sized balls, and bake for 10-15 minutes.

She wrote that

“The stars gravitate around the Sun just as the Earth attracts the creatures which inhabit it”

This is the concept of universal gravitation as we know it now, long before it became a standard part of mathematics (five hundred years later by Sir Isaac Newton). She also wrote

“If it is cold in winter time on the part of the Earth which we inhabit, then the other part must be warm, in order that the temperature of the Earth may always be in equilibrium”

adapted from Hildegard of Bingen, Symphonia Harmonie Celestium Revelationum, published in modern facsimile by Alamire, POB 45, 3990 Peer, Belgium

This shows a remarkable sense of the synergy of the Earth. Today we call this point of view thermodynamics. And forecasting Harvey’s theory of blood movement through the body as well as the concept of universal gravitation she wrote:

“Stars are not immovable but transverse the universe in a manner similar to blood moving through the body.”

My favorite quote is about her belief in the healing power of gems.

“A precious gem will heal the body if taken to bed. And a diamond held in the mouth of a liar or scold would cure any spiritual defects.”

Definitely something worth following up.

Hildegard was a special woman, talented in many, many fields. She corresponded widely with the learned men and women of the day and was highly sought after for advice. She was brave in her writings. There is a letter from her to Pope Anastasius IV that begins

“So it is, O man, that you who sit in the chief seat of the Lord, hold him in contempt when you embrace evil …”

She was one of the shining lights of the early Middle Ages. Her books were instant “bestsellers”.

Another of her beautiful illuminations is shown above.

During this time Italy continued its unique tradition of allowing women in the university. In 1236 CE Bettina Gozzadini was appointed to the Chair of Law at the University of Bologna. A century later Novella d’Andrea frequently substituted for her father, a professor of law at the same university. But more about Italy later.

As we move forward in time we find a few women who worked in traditional male occupations. Fya upper Bach was a 14th century blacksmith in Siberg, Germany. Twice in her career she held office in the local blacksmiths’ guild. Mary Sidney Herbert (1561 – 1621 CE), Countess of Pembroke, was quite a learned lady. She was known for her chemistry as well as her poems. One of the leading male chemists of the day – Adrian Gilbert – called her a chemist of note. Women were inventors too. Isabella Cunio (13th century CE) may have been the co-inventor with her brother of woodblock engraving.

It is extremely difficult to find names from the far East and India during this time. Did women of scholarship exist? I think so, but their names are deep in untranslated documents. Two names only have I found. One is the daughter of the Indian mathematician Bhasharacharya (1114 – 1185 CE). He did many important things in astronomy and mathematics including resolving a problem with the number zero. He was the first to note that division by zero did not give zero; it resulted in infinity. He wrote several texts on math, one of which he named after his daughter Leelavati (“Beautiful”). The book was used to teach her algebra. She was also an excellent mathematician. In 1816 this book was translated into English. The other is Raziya. Shortly after Leelavati lived, Raziya became the first Muslim lady to rule a Moslem state – she was Sultana of Delhi in 1236 CE and very well educated.

I shall end this chapter with a note about a woman who was not a scientist but was perhaps the first woman in Europe to earn her living through her writing – Christian de Pisan (1363 – 1429 CE) . Widowed at twenty-five with a large family to support she took the bold step of going her own way. She wrote at least twelve books and ten works in verse, including what is perhaps the first history of women in the European world – The Book of the City of Ladies. This is a fascinating book that combines legend with reality in a sweeping allegory of a city of ladies. Her works are still studied today. I found a tidbit in this book that continues to enchant me. It is a puzzling statement about the education of women.

“God has given them such beautiful minds to apply themselves, if they want to, in any of the fields where glorious and excellent men are active, which are neither more nor less accessible to them as compared to men if they wished to study them, and they can thereby acquire a lasting name…”

Did she mean that women had the same opportunities as men in the 14th century? I don’t know. It is fascinating to speculate. Nonetheless it is always true that most women and men were scrabbling for mere existence in these centuries.

The times leading to the Renaissance were times of extreme change in social customs. The black death decimated whole towns bringing cultural change with it because the plague upset the social order (especially in the 14th century, see next chapter). It was a struggle just to survive for the vast majority of people. Slowly, the Roman Catholic Church solidified its beliefs, and over time the stultifying religious view of women’s inferiority overcame the freeing winds of the convent. The Christian church consolidated its power becoming the major claimant in most peoples’ lives. Church fathers wrote polemics against women, especially women scholars. The great convents were destroyed or shut down. The profits of centuries of learning and effort were snatched away. Men shut down the convents, destroyed the manuscripts, took the money and lands and created new universities on the ashes. The great witchcraft mania began, not to end until the 18th century. Until the 14th century men and women of the feudal nobility received approximately the same elementary education. With the rise of the university system in Europe that custom declined. Where religion once supported women in scholarship, it now denied them access. One had to be a member of the clergy to attend the university, and women were denied that right.

Despite Christian de Pisan’s statement that women have such beautiful minds, rights for women declined with one large exception. Let us travel a bit further along in time.